A Swiss Adventure

Touring Switzerland

Bern

After our incredible stay in Zermatt, Julia and I boarded a train

bound for Bern. The train journey, as always in Switzerland, was smooth and

picturesque. Rolling hills, small villages, and expansive green meadows passed

by our windows as we made our way toward the capital city. We were both eager

to explore Bern, a city known not only for its historical significance but also

for its connection to one of the greatest minds in history: Albert Einstein.

Arriving in Bern felt different from the mountain villages we had

been visiting. It was a city, no doubt, but there was something wonderfully

calm and unhurried about it. The old town of Bern, with its UNESCO World

Heritage status, is packed with medieval buildings, cobblestone streets, and

covered arcades that stretch out along the streets like a continuous canopy.

Despite being the capital – well kind of –, Bern has a village-like charm that

immediately resonated with us.

Officially designated as the "federal city," Bern was

chosen as a compromise in 1848 to avoid centralizing too much power in one

region, reflecting Switzerland’s commitment to decentralization. Unlike other

capitals, Bern is not the largest or most economically powerful city in the

country, with Zurich and Geneva holding much of the financial and diplomatic

influence. So, Bern is sort of the capital of Switzerland.

We had two days in this lovely city, and we were determined to make

the most of it. Our first stop was the Federal Palace (Bundeshaus), where

Switzerland's parliament meets. The building itself is an architectural marvel,

with its neo-Renaissance design and imposing façade.

From there, we strolled through Bern’s old town, wandering along the

narrow streets, stopping in quaint shops, and admiring the town’s many

fountains—each with its own story. It was easy to lose ourselves in the beauty

of the city, and soon we found ourselves standing in front of one of Bern’s

most famous landmarks, the Berner Münster. This towering cathedral, with its

intricate Gothic architecture, was a sight to behold.

One of the highlights of our time in Bern was undoubtedly our visit

to the Einstein House. Located in the Kramgasse, this modest apartment was

where Einstein lived with his first wife, Mileva, and their son, Hans Albert,

from 1903 to 1905. It was during these years that Einstein worked at the Swiss

Patent Office, a job that gave him the time and space to work on his own

scientific ideas. This period in Bern is known as Einstein's “miracle year”

(annus mirabilis), during which he published four groundbreaking papers that

would forever change the world of physics.

Walking through the small apartment, it was amazing to think that it

was here, in such simple surroundings, that Einstein developed his special

theory of relativity. The house has been preserved to give visitors a sense of

what life was like for the young physicist at that time. The exhibits tell the

story of Einstein’s life, his time in Bern, and how his ideas evolved. One room

is filled with photographs, letters, and other personal artifacts that help

paint a picture of his life as both a scientist and a man.

What we found particularly interesting was Einstein’s journey with citizenship.

Born in the German Empire, Einstein gave up his German citizenship in 1896 and

was stateless for a few years before becoming a Swiss citizen in 1901. His

decision to move to Switzerland was partly motivated by his desire to escape

the rigid educational system in Germany, but also because Switzerland, with its

progressive attitude toward science and intellectual freedom, seemed like the

perfect place for him to grow and thrive. Bern, in particular, became a place

of refuge and creativity for Einstein during his early years, and it’s clear

that the city had a lasting impact on him. Despite his later fame and travels

around the world, he always maintained his Swiss citizenship.

The next day, we visited the Bern Historical Museum (Bernisches

Historisches Museum), which hosts the famous Einstein Museum exhibition. This

extensive collection dives even deeper into Einstein's life and work, giving a

detailed account of his scientific discoveries and their impact on the world.

The museum does an incredible job of making complex scientific ideas accessible

to the general public, using interactive displays, original manuscripts, and

historical artifacts. We spent hours exploring the exhibits, immersing

ourselves in Einstein’s life and work, from his humble beginnings in Bern to

his later years as one of the most renowned figures in the world.

While living in Bern, Albert Einstein invented a small device called

the Einstein refrigerator in collaboration with his former student Leo Szilard

in 1926. Yes, he was an inventor too – who new. This refrigerator was an

absorption refrigerator that operated without any moving parts and used only

heat as an energy source. The design was meant to be safer and more reliable

than the traditional refrigerators of the time, which used toxic gases like

ammonia, methyl chloride, and sulfur dioxide as refrigerants. Although it never

became commercially successful, the Einstein refrigerator demonstrated

Einstein’s innovative approach to problem-solving, extending beyond his

contributions to theoretical physics.

The exhibition also touched on the more personal aspects of

Einstein’s life—his complex relationships, his political views, and the

challenges he faced as both a scientist and a public figure. One of the most

moving parts of the exhibition was learning about how Einstein, a pacifist,

spoke out against war and fascism, particularly during the rise of the Nazi

regime in Germany, which led to his decision to leave Europe for the United

States. Despite all the upheaval in his later life, Einstein’s connection to

Switzerland remained strong, and it was clear that Bern had a special place in

his heart.

After two days of exploring Bern’s history and Einstein’s legacy, we

were equally impressed by the city itself. Though it is the political center of

Switzerland, Bern retains a charming and relaxed atmosphere, with its

well-preserved medieval architecture and its welcoming, easygoing vibe. One of

the things we appreciated most was how easy it was to find vegan food. We had

expected Bern to be a bit more traditional, but we were pleasantly surprised by

the number of restaurants offering plant-based options. From vegan burgers to

creative salads and hearty vegetable stews, we never had trouble finding

delicious meals.

As we prepared to leave Bern, we couldn’t help but feel a sense of

admiration for the city and its deep connection to Einstein. Bern is more than

just a political and historical hub—it’s a place where ideas were born, where

one of the greatest minds of our time found inspiration and refuge. It’s a city

that, while small in size, is grand in its significance. And for us, it will

always hold a special place in our hearts, not just for its beauty and history,

but for the quiet sense of inspiration it left with us.

Zurich

After two lovely days in Bern, it was time to make our way back to

Zurich. The train ride was comfortable, passing through picturesque Swiss

countryside, each bend revealing new vistas of rolling hills and the occasional

silhouette of distant mountains. Julia and I had grown fond of the easy travel

in Switzerland, the efficiency of the trains, and how they seemed to glide from

city to city without ever a hitch. We reminisced about our time in Bern—how the

quaint charm of the city had captured our hearts.

Arriving in Zurich, the familiar vibrancy of the city greeted us.

Zurich is the largest city in Switzerland, but what struck us wasn’t its size

but the beauty and diversity in each part of it. From the moment we walked out

of the train station, the flow of the Limmat River caught our attention, its

waters cutting a clean line through the city, bringing a sense of calm amidst

the bustling streets. We decided to start our stay with a stroll along the

river, where the medieval architecture of the city blended effortlessly with

modern buildings. It was impossible not to feel the weight of history in

Zurich. The city’s rich past seemed to flow through the streets, hidden in the

walls of ancient structures and whispered by the winds as they swept off the

lake.

Zurich’s lakefront is mesmerizing, a tranquil body of water with

sailboats drifting lazily across its surface. As we walked along the promenade,

we took in the sight of locals enjoying the sunny afternoon, some on bicycles,

others walking dogs, all soaking in the serenity of the lakeside. The view of

the distant Alps added to the splendor, though they were now a backdrop to the

urban vibrancy we were immersed in. Afterward, we meandered through the narrow,

winding streets of Zurich’s Altstadt (Old Town), with its cobblestone paths and

medieval buildings, giving the feeling that we’d stepped back in time.

One of the highlights of our time in Zurich, however, was our visit

to the Kunsthaus Zürich, the city's famed art museum. We were eager to

experience it. From the moment we stepped into the museum, it became clear that

this was more than just an art collection—it was a deep and complex reflection

of history, particularly that of the 20th century. Julia and I had read about

the museum’s connection to the controversial era of Nazi Germany, a chapter in

European history that the art world has had to confront time and again.

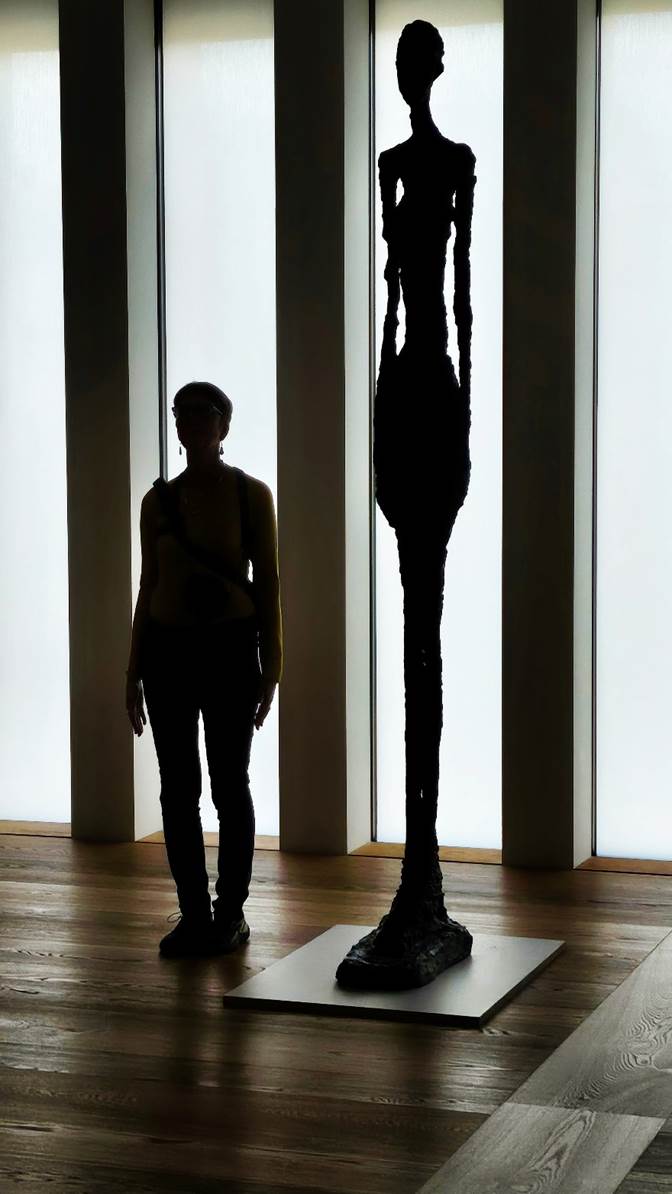

The museum’s collection is vast, covering centuries of artistic

achievement, but it was the modern European art section that drew us in the

most. We moved through rooms filled with works by Giacometti, Chagall, Munch,

and Picasso, their bold colors and striking forms speaking volumes about the

tumultuous periods in which they were created. Each painting seemed to carry

the weight of the artist's personal history, but also a collective history—one

marked by war, displacement, and loss.

One particular exhibit caught our attention, a section dedicated to

art that had been looted or confiscated by the Nazis during World War II. This

part of the museum told a darker story, one where art and politics collided in

ways that forever altered the lives of artists, collectors, and entire

families. During the Nazi regime, many Jewish collectors and artists had their

works stolen or forcibly sold under duress. The Nazis labeled much of the

avant-garde work of the time as “degenerate art,” seeking to erase what they

saw as subversive or nonconformist ideas from the cultural landscape of Europe.

Many of the pieces we were admiring in the museum had once belonged to Jewish

families, their fates tragically intertwined with the horrors of the Holocaust.

Kunsthaus Zürich, like many other major European museums, had to

confront its own involvement in the handling of looted art. While the museum is

not directly responsible for the thefts, some of the works in its collection

had questionable origins. A part of the museum’s history involves a man named

Emil Georg Bührle, a wealthy industrialist and art collector who amassed an

extraordinary collection during and after the war, some of which was later

found to have come from dubious sources. The museum houses many of Bührle’s

acquisitions, and there has been ongoing debate about the provenance of some of

these pieces.

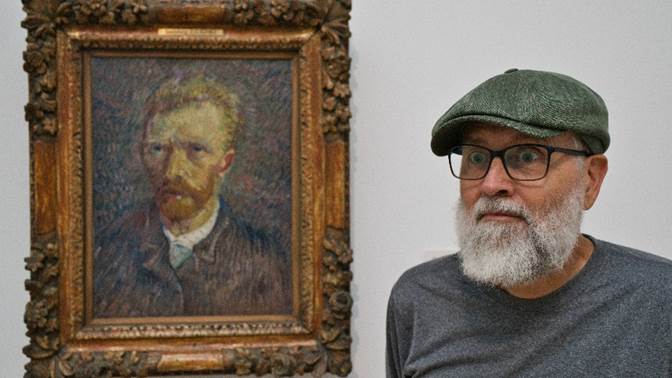

As we stood in front of one of Bührle’s acquisitions, a painting by

Van Gogh, I couldn’t help but feel a sense of unease. It was beautiful, of

course, but knowing the potential history behind it added a layer of complexity

to our experience. We discussed how museums today are taking steps to research

the provenance of their collections and return stolen art to the rightful

owners, but it is a long and often difficult process. Julia and I felt

conflicted, torn between admiration for the art and sorrow for the families who

had suffered so much loss.

Despite the difficult history, the Kunsthaus Zürich is also a place

of healing and reconciliation. In recent years, the museum has made a concerted

effort to shine a light on its more controversial pieces, openly discussing the

Bührle collection and the steps being taken to address historical wrongs. The

exhibit we were walking through was a part of that effort, with detailed

descriptions accompanying each piece, explaining its provenance, the family's

history, and the ongoing efforts to restore justice where possible. It was

humbling to witness.

Leaving the museum, we felt a sense of gratitude for the experience,

even if it left us with more questions than answers. Art, as we had been

reminded, is not only a reflection of beauty but also of human history—the good

and the bad, the triumphs and the tragedies. Zurich’s art museum embodied that

truth, standing at the crossroads of culture and history, constantly reminding

visitors of the complexities of the past.

For the remainder of our stay, we dined at some of Zurich’s

wonderful vegan restaurants, including a cozy spot near the river that served

plant-based versions of traditional Swiss dishes. We loved exploring the

culinary creativity of the city, discovering just how much Zurich had to offer

beyond its stunning views and rich history. As we prepared to leave the city

and conclude our Swiss adventure, Zurich had left an indelible mark on us—a

place where the past and the present coexist in harmony, where every corner

held a story, and where art, food, and nature came together to form a truly

unforgettable experience.