Iceland

Westland (Vesturland)

Friday, July 21, 2017

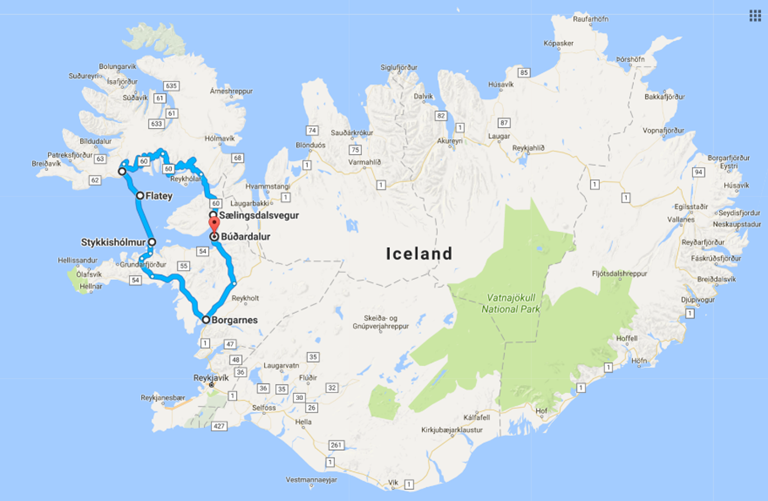

Sælingsdalsvegur to Brjánslækur to Flatey Island to Stykkishólmur to Borgarnes to Búðardalur, and then back to Sælingsdalsvegur. These were the unpronounceable Icelandic towns that made up our grand circle of the Westland of this land of fire and ice. It was a long day of driving 410 kilometers (7 hours and 30 minutes), thankfully some of it floating and not driving. It included travel on narrow roads, single-lane bridges, very rough gravel roads, and a ferry. But what we saw along this arduous route was so stunningly beautiful it was worth the effort.

Julia and I had a tiny glimpse of the magnificent Westland when we visited Ísafjörður on our trans-Atlantic Ocean cruise in 2013. Ísafjörður is a town in the very northwest of Iceland. It has a population of about 2,600 and is the largest town in the peninsula of Vestfirðir. But the grand circle we drove today exposed us to many other wonders of the Westland. Tall volcanic scree mountains covered in a bright green carpet of moss and draped in thick, ominous white cloudy mist greeted us as we entered the fjords of Breiðafjörður. There the paved road turned into rough and windy gravel tracks rife with potholes.

After bumping about the bumpy roads, we eventually came to the ferry at Brjánslækur. Here we loaded our car, sailed south to Flatey Island, and disembarked at the lovely little village of Stykkishólmur. From here, avoiding any more gravel roads, we drove back to our comfortable hotel in Sælingsdalsvegur. What a great day.

Saturday, July 22, 2017

At the time of human settlement of Iceland almost 1,150 years ago, birch forest and woodland covered 25-40% of Iceland. Birch forests in sheltered valleys slowly graded to a mix of birch and willow scrub toward the exposed wetlands near the coast. At high elevations, these lush forests were replaced by low-growing moss, lichen, and shrubs, which eventually gave way to a lifeless rocky landscape.

As in agrarian societies everywhere in the world, the settlers of Iceland began cutting down the forests to create fields and grazing land. Sheep were important as a source of wool from the outset, but by about 1300 they had become a staple source of food for Icelanders as well. At the same time, the Catholic Church (also the political power at the time) started obtaining woodland remnants, a clear indication that forests had become valuable resources because of their increasing rarity.

Sheep grazing prevented regeneration of the birch-wood forest after they had been felled. And so the woodland continued to decline. A cooling climate (the Little Ice Age) and volcanic eruptions are cited as possible alternate causes for the decline of the woodlands. But these events cannot solely explain the overall deforestation that took place. Cooling temperatures might have lowered tree line elevation, but they do not explain deforestation of the lowlands, where temperatures have been sufficient for birch-woods since the deforestation began. Natural volcanic disturbance is sporadic and limited in area and thus cannot account for the permanent destruction of 95% of the original forests. In Iceland as elsewhere, regeneration failure due to livestock grazing is the principal cause of the deforestation.

The modern Icelanders face a similar dilemma to their forefathers: how much should they sacrifice the environment of Iceland to support their population growth? Yesterday it was forests; today it is flooding habitat for hydroelectric energy production - the electricity they sell to global capitalist corporations to produce aluminum. Will they make the same mistake again and sacrifice their environment for their growth?

Capitalist economists have never factored the environment or health and safety into the real cost of production. When will we ever learn?

We left Sælingsdalsvegur behind us and drove through the treeless and electricity-drenched lands to lake Laugarvatn in the southlands.

Sunday, July 23, 2017

Driving today from Sælingsdalsvegur, our home for the last few days, to Laugarvatn in the southlands we encountered the true beauty of Iceland. It is not a soft and fluffy beauty, rather it is a rugged and rough one. It is a beauty that you feel in the chilly wind, see in deep green grass, brown craggy hills, and scree-covered volcanic mountains. But nonetheless it is a beauty that invades your soul.

Along our route we stopped at the cindered remains of the volcanic aftermath at Grábrók. Cinder cones, lava, and devastation fill this place and directly remind you of what Iceland is.

In Borgarbyggð we stopped for the obligatory latte and exposed ourselves to a very underwhelming Icelandic history museum. The history of Iceland is rich and complicated. It's too bad that this museum did not communicate this richness.

Monday, July 24, 2017

Thingvellir National Park is a flat expanse of land covered by wild geraniums and many other wildflowers and shrubs. This vast flatland is framed by Lake Thingvallavatn, high volcanic mountains, and the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates. Enormous underground tectonic forces push these two mammoth land masses apart at a rate of two centimeters a year. In a world that is literally pushing itself apart, Thingvellir National Park is serene, peaceful, and unaware of it all.

Drinking beer in a geothermally heated spa, overlooking a deep-blue lake, is the best way to relax after a long day of hiking and touring. This is exactly what Julia and I did to end this great and glorious day.

Tuesday, July 25, 2017

Just down the road from our hotel (a school in the winter months) at Laugarvatn is the Strokkur geothermal area. This is the Yellowstone of Iceland, right down to a rhythmic geyser erupting with expulsions of steam and water every three to six minutes. It's odd, but waiting to see a geyser explode is simply fascinating. Of course, the place was filled with tourists, but we are tourists too, after all.

A little further down the road, known by locals as the Golden Circle, is the Gullfoss waterfall. This enormous cascade of water is driven by a massive river, which is fed by a gigantic slab of ice and snow - the Langjökull glacier. Just like watching geysers, gazing at immense waterfalls is also hypnotic to tourists, and so this place was inundated by them too.

Leaving the throng of sightseeing-hungry tourists behind us, we drove to the remote little hamlet of Flúðir. There's not much there - a campground, some homes, a few shops - but they have great food there. This was an amazing place to have lunch and continue our impressive culinary experiences in Iceland.

Once back at Laugarvatn we hiked through the (extremely rare) stand of trees at the foot of a colossal volcanic ash and frozen lava mountain.

During our short hike, my faithful and reliable hiking boots of 20 years exploded. The sole completely came off one of the trusty boots and left me to hobble back. Well, I did get 20 years of wear out of them, and they had been around the world several times. Goodbye old friends.

This loop led us through a shaded pine tree forest and eventually back to our relaxing spa and beer ritual.

Wednesday, July 26, 2017

The great PIN conspiracy continues. In the last two or perhaps three years, chip-and-PIN credit cards were introduced in the USA. I thought this a great step forward for the USA, even though the rest of the world has been using this system for years now. But alas, the USA-based chip-and-PIN system does not work like the rest of the world's, and so we continue to require a signature to authorize a purchase when using the USA chip-and-PIN system overseas.

A luxury problem, you say? Well in Iceland, remote gas stations have no attendants. Many of them are fully automated and often very remote. Your only option is to use what Icelanders call the AutoMat. The AutoMat requires your card to have a chip and a PIN - and not just the rubbish US PIN, but a proper PIN. No PIN, no gas.

As we moved ever closer to the airport at Keflavík and our imminent departure from the land of fire and ice, black sand beaches of the southern coast of Iceland rolled out before us. We walked the dark sands, ate a delicious lunch, and said farewell to Iceland. We left this afternoon for the Emerald Isles of Ireland.

Wow Air sucks beyond sucking. The flight was an hour late to leave, the boarding was disorganized and confusing, and the seats on the aircraft could have been used by the Spanish Inquisition. But you get what you pay for.

Goodbye Iceland.

Many things were lost on this trip. We did not get to see Greenland, and we left behind two good friends.